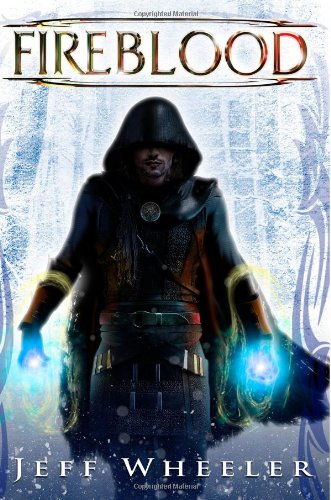

Jeff Wheeler's novel Fireblood is the first volume of his Whispers of Mirrowen series. Like his Muirwood series, it spans three books. Unlike the Muirwood series, its three volumes didn't share a single publication date: readers wanting the whole tale will have to wait until the third volume is published in the future.

This leads to my first gripe: like Connie Willis' time-travel story comprising Blackout and All Clear, no one volume tells a complete story. When I read Blackout, I immediately realized that without access to its sequel I'd have been incensed to have been led into a book thinking I was getting a story, only to find it cut short with no resolution to any part of it. I felt I'd been sold the result of one good book being fed through a buzz saw and vended in halves. That's not to say the story isn't delightful and moving, but for safety's sake don't pick up Blackout without easy access to All Clear. To be fair, cutting stories into bits and selling them in different volumes isn't new in fantasy. Tolkein's Lord of the Rings trilogy may have enshrined the practice from the genre's very beginning. But it's this reviewer's fervent hope that writers will see what Jim Butcher has proved with his two separate fantasy series, each of which is comprised only of novels that tell satisfying and complete stories: people love to read reliably good stories and will buy them if you prove you can write them reliably, especially if you keep the same characters alive and evolving and interesting for fifteen volumes (and in the Dresden Files, heading past twenty). But this is a gripe. People read the Lord of the Rings, and they read the Oxford time travel books, and they'll keep reading volumes that don't tell complete stories so long as they feel confident the whole story will satisfy.

What's Right

Fireblood does several good things.

Unlike so many fantasy worlds, Whispers of Mirrowen decouples race from culture. This doesn't sound like a big innovation, but the result is a much more complex social fabric in which national politics, social competition, and racial tension give a full-color feel to motives and enmities that in other worlds are simplified into elf/dwarf rivalry. Mind you, elf/dwarf rivalry worked okay for Terry Brooks in Wishsong of Shannara when readers were already committed to the story and distracted with other concerns, but the fewer things one must suspend disbelief about, the easier it is to get lost in the story. And isn't that why we're reading it anyway? (What did Brooks' elves and dwarves do to each other that we believe it?)

Whispers of Mirrowen offers interesting magic. Many types exist, each with different costs and limitations. Since races and cultures cross boundaries of politics and faith, the powers that work for protagonists also work in equal measure against them. What readers learn about magic when it's working for protagonists hangs over the reader, creating tension as we see antagonists access the same kinds of powers.

Characters have believable conflicts, including among protagonists. In several places one wonders whether villains will derail protagonists, or their own squabbles and fears. Wheeler's third-person narrative shifts of focus between characters so readers can see enough of what characters secretly think and dream when they're alone to help them understand the collision of motives, but it leaves enough unexplained to raise tension when the collisions occur.

Content Alert

Jaded Consumer fiction reviews traditionally contain a variety of "content warnings" regarding various aspects of works. The warnings aren't for everyone, and need not keep people from finding work an enjoyable read. Whether it involves politics or religion or merely an optimistic outlook on the human condition, content alerts aren't intended to damn work but to alert people whose tastes run in another direction.

As intimated in the note above about the story-incomplete volumes in this series, it's the Jaded Consumer's conclusion that Jeff Wheeler read Tolkien. Maybe … maybe the wrong way. Here, the Jaded Consumer refers to the pace of the work. For instance, the first chapter introduces a character whose band of adventurers has been slaughtered down to a single ally and left stranded in the deepest depths of hostile territory, just as they're found by undescribed awful clawed things. One would think his lost-ness and desperation would lead the chapter – they are what makes it interesting, and what must draw the reader if anything does. They're the hook, right? But, no. Fireblood opens with the weather. This appears an intentional artistic decision – apparently for structure; the chapter closes with the weather, to which the scene outcome is attributed. Once the real problem in the scene became evident, I wondered why it was I didn't care about the protagonists' desperate plight. It felt buried in description to which I had no emotional connection. The rest of the book picks up. But as in Tolkien, sentences avoid quick subject-object-verb structure; the ideas curve lengthily about dependent clauses and description that feel like they insulate one from the story's grip.

And it's got a grip. This is a story I'd like to see finished (see above; this is not the first story in a three-story episode arc, it's the first segment of a single story cut into three pieces). People who require modern stories' fast pace may not want to stick with something written with the slow description of a book from another age.

Toward the end of the book, the story's grippiness takes another blow as the big mysteries behind the current conflict are revealed to the protagonists (and the reader). It comes as description, with long dialogue giving secondhand encapsulation of facts that sound like they'd be exciting to see firsthand. When Rowling faced the burden of heavy exposition in her Harry Potter series, she invented a fantasy gizmo that allowed him to see events firsthand – so the reader would see the action with the protagonist, instead of merely hearing about it. Fireblood's pace takes a hard blow under the weight of heavy exposition.

Culture Shock

I enjoy the multiple fantasy cultures depicted in Fireblood, but one bothered me. Fireblood depicts a "Romani" people that appears to echo the worst stereotypes of the real-world Gypsies/Roma/Romani, down to child-stealing, human trafficking, misogyny, and an ostensibly pervasive culture of criminal enterprise. This is a fantasy world; why do we need to trade on prejudices against a real-world ethnic minority? It'd be easier to hate them as the author wants, if we weren't worried we were being urged against a real people nearly exterminated in some parts of the world by people preaching their difference.

Back To Our Scheduled Programming

Fireblood's sympathetic characters' intractable problems lead them not only into each other's orbit, but into inevitable conflict. It's not trivial conflict, but feels important – not just to the characters, but their world. If the characters weren't interesting, one wouldn't care. If the stakes weren't interesting, one wouldn't care. Wheeler gives readers a real invitation to follow the story he weaves.

Conclusion

If you're suited to the pace, Fireblood offers a complex world full of interesting problems for characters that are easy to like.

No comments:

Post a Comment