Wednesday, March 18, 2015

RIP Internet Explorer

Microsoft is killing its Internet Explorer brand. Maybe because anyone who knew better snickered at it? Codenamed Spartan, the next browser from Microsoft should suck less. How could it not? Hopefully for victims users the revolution is more than skin deep.

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

Berkshire: High Growth?

Seeking Alpha recently published the Jaded Consumer article "Berkshire Hathaway: High Growth Stock?" To get another view on this, look at Berkshire vs Microsoft chart in "Apple's Future After Joining Dow: Brighter Than Microsoft's", which compares Berkshire to Microsoft in the decade and a half following Microsoft's addition to the Dow. Solid >8% annualized performance at Berkshire trounced the global desktop OS leader over the period.

Apple's Future After Joining Dow: Brighter Than Microsoft's

Last week, Apple Inc. (once known as "Apple Computer Inc.") replaced AT&T in the stock index called the Dow Jones Industrial Average. (The author says "called" because it is not, in fact, an average.) The responses to this - ranging from "Apple is doomed" through "So what?" to "Yay, index funds now have to buy Apple!" - largely overlook the fundamentals that will drive whatever future Apple will provide its investors. This article contrasts Apple's position to the future that lay before Microsoft Corp. when it joined the Dow in 1999.

Numbers

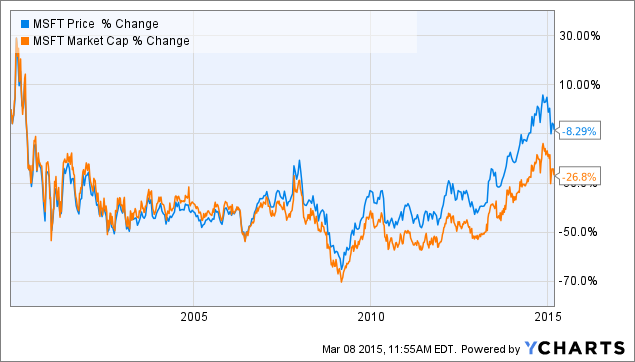

From November 1, 1999 (the date MSFT joined the Dow) through last Friday, Microsoft's stock's ups and downs landed it down over 8%. Since its market cap declined even faster, it's clear the current price benefited from its share buyback program, without which the company's declining market cap would have left each share down more than three times that much:

Microsoft has paid dividends since 2003. After an annual dividend of 8¢/sh in its fiscal 2003 and one of 16¢/sh in its fiscal 2004, Microsoft paid a $3 special dividend in December of 2004 a regularly quarterly dividend thereafter. Including 31¢/sh payable March 12. 2015, Microsoft's dividend history - since the inception of dividends in 2003 - paid shareholders who held over the period a total of $9.97. Added to Microsoft's Friday close of $42.36, this puts holders for the period at $52.33, up from its split-adjusted close on November 1, 1999, of $32.87 - a total return (before taxes) of $19.46 (59.2%), or nearly 3.1% annualized over the period. Although this initially looks better than the ~47% return of the S&P 500 over the period …

… it doesn't match the S&P 500 period return with dividends (>90%, and >4% annualized). Although Microsoft's dividend has been reliable since its inception - enough to beat its stock price decline - its competitor Hewlett Packard Co. began paying dividends earlier, putting Microsoft only modestly ahead over the period compared in investors in its biggest publicly-traded OEM vendor.

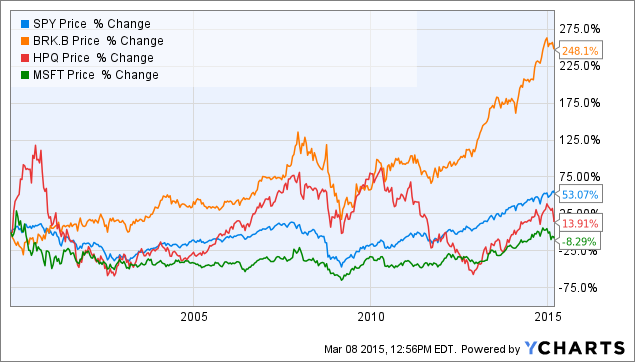

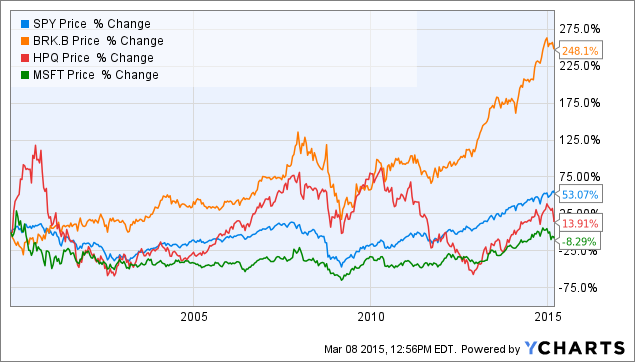

The apparent yield of Microsoft in 2005 results from its $3 special dividend in December of 2004; it never had a double-digit dividend yield. YCharts presents a total-return chart showing returns adjusted for dividends as they're paid, showing the relative performance of Microsoft, its largest remaining US-listed OEM vendor, the S&P 500 (because it's a common benchmark), and Berkshire Hathaway Class B (BRK.B)(because it's a widows-and-orphans investment always worth comparing to anything):

Annualizing these numbers over the decade and a half period since Microsoft joined the Dow renders them fairly modest. Berkshire's total return of 248.1% annualizes to a bit over 8%, which isn't bad considering the market dislocations of 2001 and 2008. The fact that investing in a tech giant like Microsoft would fail to beat the S&P 500 probably came as a surprise to high-conviction long-term investors certain Microsoft would continue to dominate the world in market cap as it once did.

What Microsoft Was Up To When It Joined The Dow

To understand Microsoft's lackluster performance as a Dow component, it's not enough to nod knowingly and say that it'd grown too big. When Apple passed Microsoft in market cap on May 26, 2010, mathematical law didn't halt its outperformance. Far from it:

(The total return chart reflects both companies' dividends.)

To understand why Microsoft's performance in the early 2000s held the company back, it's necessary to look at what it was doing to grow at the time. In 1999, Microsoft owned the PC desktop operating system market and held a hugely profitable share of the market for server operating systems and tools, and was just deciding to make gaming consoles, a loss-leader business in which it only lost money until 2004. Its zeal to obtain a monopoly in digital music formats and to secure royalties from every music player in every car, home stereo, and Walkman, Microsoft drove Apple into music players and inspired Apple's Music Store to protect Apple's customers from losing access to new music promised by Microsoft's threatened era of Microsoft-only music formats. Frightened of losing control of servers to virtualization firms like VMWare, Microsoft bought VirtualPC from Connectix Corp. (now dissolved) and rewrote its already-complicated licenses to charge customers a premium if they wanted to install Microsoft's products on virtual servers - something high-uptime management makes mandatory. In doing so, it raised OEM and customer incentive to consider alternatives. When Microsoft's FUD campaign against Apple music players failed, Microsoft gave up securing music file format hegemony through its PC model (i.e., having OEMs make hardware while licensing its software at little cost to Microsoft), and leapt into the portable music player market only to abandon it. Microsoft created, marketed, and abandoned a Microsoft eBook reader, only to fund an eBook venture with Barnes & Noble Inc. (BKS) in which Microsoft lost hundreds of millions before bailing out in December.

Meanwhile, Microsoft made its operating systems costlier for OEMs to deploy on desktops. It also complicated its OS licensing scheme to ensure that while it would hold the bottom end share (to prevent encroachment by newcomers), it would profit much more from the higher-end market segment and command a premium from enterprises and pro users who depended on highly parallel application operation, remote administration, and access to networks through centrally-controlled credentialing systems. While working to leverage its OS monopoly into earnings growth, it saw mobile platforms grow in relevance - non-Microsoft mobile platforms that offered competitors a foothold in bringing developers and customers from dependence on Microsoft-controlled APIs, developer tools, and licensing fees. Microsoft's mobile device licensing fees drove mobile OEMs to competitive platforms, but mobile hardware is a cut-throat business and Microsoft optimistically cheered while firms with an established history making and marketing hardware were driven from the field. (Whether Microsoft cheered oblivious to its own plight or to distract attention from it is your guess.)

Apple's entry into smartphones in 2007 changed the face of mobile competition. Besides Apple, only the world's unit sales leader profited in the smartphone market. But Apple added to its hardware complete control over the software it shipped, so that it produced superior performance for users even in areas in which its hardware specs arguably lagged. Competing with Apple required vendors to invest their own resources in their mobile OS development, reducing margins on a device count that could not compete with Apple's comparable products. (The bulk of the smartphone market consists of cheaper, lower-margin phones whose hardware wouldn't compete even with software customization.)

Eleven years after joining the Dow, Microsoft used expertise it acquired with the Danger acquisition to launch its own phone hardware in May of 2010 - but it didn't effectively market the phone's greatest strength (cloud backup) and failed to include features users had come to depend on in the profitable segment of the phone market. The billion-dollar Danger acquisition led to a major product flop. (Apple had product flops, too - as described here. Marketing isn't everything.) After subsidizing Nokia Oyj to produce hardware shipping a Microsoft mobile OS, Microsoft purchased Nokia's hardware division only to share a non-iOS/non-Android global share of 4% with such struggling competitors as Blackberry Ltd. (formerly Research In Motion, which approved a sale of itself to a third party a few years ago but was apparently stymied by regulators) and Jolla Ltd. (privately-held 125-employee vendor of the Sailfish OS). On the way to this ignominious position, Microsoft had to endure headlines like "Samsung's Bada OS growing faster than Windows Phone". (Samsung merged Bada's best components into the Linux-based Tizen project, with which Samsung - much like Microsoft - hopes against the odds to take the "third choice" OS spot behind the market leaders.) Using Nokia to sell phones probably looked better then it still led global cellphone unit sales, but recently it's been struggling only to lose not only share but absolute sales.

What Apple is Doing As It Joins the Dow

Apple earns more profit than all other smartphone vendors combined, and the smartphone market remains a growing market. In the first quarter of 2014, only Apple and Samsung profited selling smartphones: together, they shared 106% of the global smartphone profit. The also-rans - including Microsoft - lost money to stay in the game. The interesting fact is that Apple made most of this money - 65% - while holding less than 16% unit sales share. In the last calendar quarter of 2014, Apple's phones reportedly raked in 89% of the world's smartphone profit even as the profit pie grew.

Apple is doing this while selling a minority of global units. Not only is the market growing, but Apple hasn't come anywhere near saturation.

Even as Microsoft commands the majority of the market for PC operating systems, Apple makes more profit than any of Microsoft's OEMs despite holding relatively modest share. In the last quarter of 2012, Apple's computers took 45% of the PC market's profits while selling but 5% of the PC units. By the third quarter of 2014, Apple grew PC profits to 50% of global share on the same 5% unit share. This isn't the result of some flash-in-the-pan Mac fad but of the market segment Apple pursues - what ZDNet called "the only segment of the PC market that still matters". And by holding a sizeable minority of this richest segment, Apple not only establishes itself among those who need machines in that segment but establishes a base from which to grow its reach into that segment.

Unlike Microsoft, Apple hasn't joined the Dow controlling a saturated low-growth market that forces it to look toward loss-leader markets like game consoles for growth. Apple didn't enter music players or phones with the idea of losing money to gain share, or even profiting on a razor-and-blades model of earning back on content what was lost on hardware. Apple makes good money on its hardware, and keeps post-sales revenue as pure gravy. And it's an interesting gravy market. After selling $10 billion through the App Store in 2013, App Store revenue grew 50% in 2014 - during which Apple paid developers $10 billion. While this may be modest in the scale of Apple's overall revenue, the key is to consider what this does to Apple's ecosystem: Apple developers have earned $25 billion from iOS development alone. What developer would leave a market like that? Apple's successful after-sales program ensures developers target Apple platforms first and support them with the most engineering resources. The points made in 2012 about Apple's ability to tempt developers with a user base that pays for and updates software remain valid. By building MacOS X - and therefore iOS - upon a Cocoa environment that allows a single application to support an unlimited number of languages, Apple built international support into every product it sold since departing MacOS 9. As a result, Apple's products enjoy predictably hard-to-satisfy demand in markets - like China - in which Apple couldn't compete at all when Microsoft joined the Dow.

As Apple continues to thrive in its high-margin market segment, Apple puts devices in the hands of customers with a proven willingness to pay for quality. As predicted in 2011, Apple expanded its iOS electronic wallet system into a payment processing business. Since the ApplePay rollout, Whole Foods Market Inc. saw "significant growth" in mobile payment use with double-digit week-over-week growth of ApplePay volumes and 400% growth in mobile payments by the end of January. In under a month, Apple had 1% of Whole Foods' entire transaction volume. By the end of January 2015, ApplePay accounted for 80% of all mobile payments at Panera Bread Co. (PNRA). Three months into the product's launch, ApplePay handles $2 of every $3 spent through contactless payment across the three largest card networks in the U.S. ApplePay's security doesn't keep card-issuing banks from foolishly believing fraudsters actually hold the bank's cards, but since each issuing bank sets the procedure it will use to determine whether an ApplePay user is its authorized card holder, this should improve. The ApplePay global rollout is still underway. But since Apple's mobile customers outspend competitors' customers, Apple stands to participate in a prime section of the payment processing market. Despite having a smaller number of users, iOS devices drove five times Android users' spending between Black Friday and Christmas last year. Not only were purchases more frequent, but average purchase size doubled on iOS. Whatever might be said about Samsung's mobile payment platform, it's Apple's customers that will make its payment processing more profitable.

And that's not the only growing business. Apple's "hobby" in AppleTV poises it to assault a multibillion-dollar television market while vending content. Apple's also about to launch a smartwatch, which Piper Jaffray said would face disinterest as only 14% of those surveyed would buy one for $350 without having been able to see or use it (up from 12% in an earlier poll). No disrespect, but if 14% of those surveyed would buy a product for $350 without being able to see or use it beforehand, this is either a very acquisitive demographic that's being surveyed or there's a shocking demand for an Apple watch. Most of us tell time on our phones, no? Recall, if you will, that Apple first entered the phone business with an ambition of gaining 1% of the cellphone market.

In the last quarterly results announcement, Apple guided to a March-ending quarterly revenue between $52-55 billion. At the top end, this represents 20% growth over the year-ago quarter, even accounting for foreign-currency headwinds.

Conclusion

Adding Apple to the Dow may result in some transient sales as funds adjust holdings, but the real returns will follow Apple's performance. Unlike Microsoft when it joined the Dow in 1999, Apple stands at a high-growth period that starts with a projected growth in this March-ending quarter of some 20% over the comparable quarter last year. Apple continues to strengthen its high-margin product segments even as it grows the value of its ecosystem through post-sales opportunities. Rather than descending into low-margin market segments in the quest for growth as Microsoft did following its addition to the Dow, Apple is still growing its most high-margin businesses while adding mechanisms to improve post-sales revenues opportunities. Apple isn't dead after being added to the Dow, but very much alive - and represents much better deal than Microsoft did when it joined the Dow at the end of the millennium.

Numbers

From November 1, 1999 (the date MSFT joined the Dow) through last Friday, Microsoft's stock's ups and downs landed it down over 8%. Since its market cap declined even faster, it's clear the current price benefited from its share buyback program, without which the company's declining market cap would have left each share down more than three times that much:

Microsoft has paid dividends since 2003. After an annual dividend of 8¢/sh in its fiscal 2003 and one of 16¢/sh in its fiscal 2004, Microsoft paid a $3 special dividend in December of 2004 a regularly quarterly dividend thereafter. Including 31¢/sh payable March 12. 2015, Microsoft's dividend history - since the inception of dividends in 2003 - paid shareholders who held over the period a total of $9.97. Added to Microsoft's Friday close of $42.36, this puts holders for the period at $52.33, up from its split-adjusted close on November 1, 1999, of $32.87 - a total return (before taxes) of $19.46 (59.2%), or nearly 3.1% annualized over the period. Although this initially looks better than the ~47% return of the S&P 500 over the period …

… it doesn't match the S&P 500 period return with dividends (>90%, and >4% annualized). Although Microsoft's dividend has been reliable since its inception - enough to beat its stock price decline - its competitor Hewlett Packard Co. began paying dividends earlier, putting Microsoft only modestly ahead over the period compared in investors in its biggest publicly-traded OEM vendor.

The apparent yield of Microsoft in 2005 results from its $3 special dividend in December of 2004; it never had a double-digit dividend yield. YCharts presents a total-return chart showing returns adjusted for dividends as they're paid, showing the relative performance of Microsoft, its largest remaining US-listed OEM vendor, the S&P 500 (because it's a common benchmark), and Berkshire Hathaway Class B (BRK.B)(because it's a widows-and-orphans investment always worth comparing to anything):

Annualizing these numbers over the decade and a half period since Microsoft joined the Dow renders them fairly modest. Berkshire's total return of 248.1% annualizes to a bit over 8%, which isn't bad considering the market dislocations of 2001 and 2008. The fact that investing in a tech giant like Microsoft would fail to beat the S&P 500 probably came as a surprise to high-conviction long-term investors certain Microsoft would continue to dominate the world in market cap as it once did.

What Microsoft Was Up To When It Joined The Dow

To understand Microsoft's lackluster performance as a Dow component, it's not enough to nod knowingly and say that it'd grown too big. When Apple passed Microsoft in market cap on May 26, 2010, mathematical law didn't halt its outperformance. Far from it:

(The total return chart reflects both companies' dividends.)

To understand why Microsoft's performance in the early 2000s held the company back, it's necessary to look at what it was doing to grow at the time. In 1999, Microsoft owned the PC desktop operating system market and held a hugely profitable share of the market for server operating systems and tools, and was just deciding to make gaming consoles, a loss-leader business in which it only lost money until 2004. Its zeal to obtain a monopoly in digital music formats and to secure royalties from every music player in every car, home stereo, and Walkman, Microsoft drove Apple into music players and inspired Apple's Music Store to protect Apple's customers from losing access to new music promised by Microsoft's threatened era of Microsoft-only music formats. Frightened of losing control of servers to virtualization firms like VMWare, Microsoft bought VirtualPC from Connectix Corp. (now dissolved) and rewrote its already-complicated licenses to charge customers a premium if they wanted to install Microsoft's products on virtual servers - something high-uptime management makes mandatory. In doing so, it raised OEM and customer incentive to consider alternatives. When Microsoft's FUD campaign against Apple music players failed, Microsoft gave up securing music file format hegemony through its PC model (i.e., having OEMs make hardware while licensing its software at little cost to Microsoft), and leapt into the portable music player market only to abandon it. Microsoft created, marketed, and abandoned a Microsoft eBook reader, only to fund an eBook venture with Barnes & Noble Inc. (BKS) in which Microsoft lost hundreds of millions before bailing out in December.

Meanwhile, Microsoft made its operating systems costlier for OEMs to deploy on desktops. It also complicated its OS licensing scheme to ensure that while it would hold the bottom end share (to prevent encroachment by newcomers), it would profit much more from the higher-end market segment and command a premium from enterprises and pro users who depended on highly parallel application operation, remote administration, and access to networks through centrally-controlled credentialing systems. While working to leverage its OS monopoly into earnings growth, it saw mobile platforms grow in relevance - non-Microsoft mobile platforms that offered competitors a foothold in bringing developers and customers from dependence on Microsoft-controlled APIs, developer tools, and licensing fees. Microsoft's mobile device licensing fees drove mobile OEMs to competitive platforms, but mobile hardware is a cut-throat business and Microsoft optimistically cheered while firms with an established history making and marketing hardware were driven from the field. (Whether Microsoft cheered oblivious to its own plight or to distract attention from it is your guess.)

Apple's entry into smartphones in 2007 changed the face of mobile competition. Besides Apple, only the world's unit sales leader profited in the smartphone market. But Apple added to its hardware complete control over the software it shipped, so that it produced superior performance for users even in areas in which its hardware specs arguably lagged. Competing with Apple required vendors to invest their own resources in their mobile OS development, reducing margins on a device count that could not compete with Apple's comparable products. (The bulk of the smartphone market consists of cheaper, lower-margin phones whose hardware wouldn't compete even with software customization.)

Eleven years after joining the Dow, Microsoft used expertise it acquired with the Danger acquisition to launch its own phone hardware in May of 2010 - but it didn't effectively market the phone's greatest strength (cloud backup) and failed to include features users had come to depend on in the profitable segment of the phone market. The billion-dollar Danger acquisition led to a major product flop. (Apple had product flops, too - as described here. Marketing isn't everything.) After subsidizing Nokia Oyj to produce hardware shipping a Microsoft mobile OS, Microsoft purchased Nokia's hardware division only to share a non-iOS/non-Android global share of 4% with such struggling competitors as Blackberry Ltd. (formerly Research In Motion, which approved a sale of itself to a third party a few years ago but was apparently stymied by regulators) and Jolla Ltd. (privately-held 125-employee vendor of the Sailfish OS). On the way to this ignominious position, Microsoft had to endure headlines like "Samsung's Bada OS growing faster than Windows Phone". (Samsung merged Bada's best components into the Linux-based Tizen project, with which Samsung - much like Microsoft - hopes against the odds to take the "third choice" OS spot behind the market leaders.) Using Nokia to sell phones probably looked better then it still led global cellphone unit sales, but recently it's been struggling only to lose not only share but absolute sales.

What Apple is Doing As It Joins the Dow

Apple earns more profit than all other smartphone vendors combined, and the smartphone market remains a growing market. In the first quarter of 2014, only Apple and Samsung profited selling smartphones: together, they shared 106% of the global smartphone profit. The also-rans - including Microsoft - lost money to stay in the game. The interesting fact is that Apple made most of this money - 65% - while holding less than 16% unit sales share. In the last calendar quarter of 2014, Apple's phones reportedly raked in 89% of the world's smartphone profit even as the profit pie grew.

Apple is doing this while selling a minority of global units. Not only is the market growing, but Apple hasn't come anywhere near saturation.

Even as Microsoft commands the majority of the market for PC operating systems, Apple makes more profit than any of Microsoft's OEMs despite holding relatively modest share. In the last quarter of 2012, Apple's computers took 45% of the PC market's profits while selling but 5% of the PC units. By the third quarter of 2014, Apple grew PC profits to 50% of global share on the same 5% unit share. This isn't the result of some flash-in-the-pan Mac fad but of the market segment Apple pursues - what ZDNet called "the only segment of the PC market that still matters". And by holding a sizeable minority of this richest segment, Apple not only establishes itself among those who need machines in that segment but establishes a base from which to grow its reach into that segment.

Unlike Microsoft, Apple hasn't joined the Dow controlling a saturated low-growth market that forces it to look toward loss-leader markets like game consoles for growth. Apple didn't enter music players or phones with the idea of losing money to gain share, or even profiting on a razor-and-blades model of earning back on content what was lost on hardware. Apple makes good money on its hardware, and keeps post-sales revenue as pure gravy. And it's an interesting gravy market. After selling $10 billion through the App Store in 2013, App Store revenue grew 50% in 2014 - during which Apple paid developers $10 billion. While this may be modest in the scale of Apple's overall revenue, the key is to consider what this does to Apple's ecosystem: Apple developers have earned $25 billion from iOS development alone. What developer would leave a market like that? Apple's successful after-sales program ensures developers target Apple platforms first and support them with the most engineering resources. The points made in 2012 about Apple's ability to tempt developers with a user base that pays for and updates software remain valid. By building MacOS X - and therefore iOS - upon a Cocoa environment that allows a single application to support an unlimited number of languages, Apple built international support into every product it sold since departing MacOS 9. As a result, Apple's products enjoy predictably hard-to-satisfy demand in markets - like China - in which Apple couldn't compete at all when Microsoft joined the Dow.

As Apple continues to thrive in its high-margin market segment, Apple puts devices in the hands of customers with a proven willingness to pay for quality. As predicted in 2011, Apple expanded its iOS electronic wallet system into a payment processing business. Since the ApplePay rollout, Whole Foods Market Inc. saw "significant growth" in mobile payment use with double-digit week-over-week growth of ApplePay volumes and 400% growth in mobile payments by the end of January. In under a month, Apple had 1% of Whole Foods' entire transaction volume. By the end of January 2015, ApplePay accounted for 80% of all mobile payments at Panera Bread Co. (PNRA). Three months into the product's launch, ApplePay handles $2 of every $3 spent through contactless payment across the three largest card networks in the U.S. ApplePay's security doesn't keep card-issuing banks from foolishly believing fraudsters actually hold the bank's cards, but since each issuing bank sets the procedure it will use to determine whether an ApplePay user is its authorized card holder, this should improve. The ApplePay global rollout is still underway. But since Apple's mobile customers outspend competitors' customers, Apple stands to participate in a prime section of the payment processing market. Despite having a smaller number of users, iOS devices drove five times Android users' spending between Black Friday and Christmas last year. Not only were purchases more frequent, but average purchase size doubled on iOS. Whatever might be said about Samsung's mobile payment platform, it's Apple's customers that will make its payment processing more profitable.

And that's not the only growing business. Apple's "hobby" in AppleTV poises it to assault a multibillion-dollar television market while vending content. Apple's also about to launch a smartwatch, which Piper Jaffray said would face disinterest as only 14% of those surveyed would buy one for $350 without having been able to see or use it (up from 12% in an earlier poll). No disrespect, but if 14% of those surveyed would buy a product for $350 without being able to see or use it beforehand, this is either a very acquisitive demographic that's being surveyed or there's a shocking demand for an Apple watch. Most of us tell time on our phones, no? Recall, if you will, that Apple first entered the phone business with an ambition of gaining 1% of the cellphone market.

In the last quarterly results announcement, Apple guided to a March-ending quarterly revenue between $52-55 billion. At the top end, this represents 20% growth over the year-ago quarter, even accounting for foreign-currency headwinds.

Conclusion

Adding Apple to the Dow may result in some transient sales as funds adjust holdings, but the real returns will follow Apple's performance. Unlike Microsoft when it joined the Dow in 1999, Apple stands at a high-growth period that starts with a projected growth in this March-ending quarter of some 20% over the comparable quarter last year. Apple continues to strengthen its high-margin product segments even as it grows the value of its ecosystem through post-sales opportunities. Rather than descending into low-margin market segments in the quest for growth as Microsoft did following its addition to the Dow, Apple is still growing its most high-margin businesses while adding mechanisms to improve post-sales revenues opportunities. Apple isn't dead after being added to the Dow, but very much alive - and represents much better deal than Microsoft did when it joined the Dow at the end of the millennium.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)