From Chapter One, Amelie Howard's young-adult novel The Almost Girl effectively employs elements from the reader's own youth to give a familiar feel to an unusual teen's underslept, overscheduled life in a new school surrounded by people she neither knows nor understands in a world that has much bigger problems than the semester project she learns is half her physics grade. The disconnected teen we've known if not been becomes the building block for the reader's view into a coldhearted killer from another universe, sent here to blend with teens while evading military-designed fast-zombies – no, no, she says there are no zombies … but the commandos she used to lead before being given her secret mission are against her now and she must change gears rapidly from ninja warrior to vapid schoolchild as she tries not to lose her prize to other hunters.

Why To Read The Almost Girl

The strength of The Almost Girl is its use of what we already know to evoke our feelings. Who hasn't known tattling teacher's pets, naïve goodhearted victims, thuggish jocks, scowling and territorial popularity queens, and teens who notice with great force when an empty room has only a boy and a girl in it? The protagonist's alienness makes all the more credible her alone-ness, her separation from the rest of the world, the weight of what she's doing alone – things we've already sensed from the elements painted with the familiar experiences found in teen life. The fact the protagonist's stakes involve an inter-dimensional war and the life of a dying prince and so forth merely amplify and explain the anxieties and fears Howard paints with our own experience. Who hasn't seen – or been – a student called on the carpet before a teacher? Who hasn't been busted by a parent, smooching in a house thought to be empty? Come on, you at least came close. You've been there. You'll feel it, too.

You'll also feel the personal betrayal and guilt and pride and anger in the various relationships Howard provides with siblings, acquaintances, your best friend, incomprehensible parental figures, and seemingly everything else you did and knew as a teen. Howard leverages this to great effect, so we feel the peculiar fear of being identified, caught, and punished each time we're led into another episode that echoes in our own lives. Howard depicts relationships and interpersonal tensions with great mastery. The author gently pulls the curtain on certain scenes before they go too far for a YA audience, or else fuzzes the camera so we don't get detail you couldn't notice through frosted glass, but this does nothing to impair our view of the conflicts that drive the story.

Howard appears to understand completely that what makes a story work is the characters, their conflicts, and keeping the reader in sympathy with the plight of the protagonist. And make no mistake: this book is about the characters and their insecurities and triumphs in the face of shifting circumstances and relationships and allegiances. If the story closed on an unambiguous Happily Ever After, there might not be a sequel. But the narrator is ambitious and driven so, in a tragic tradition dating back thousands of years, risks the rewards she's fought to win in a bid to fulfill her sense of mission despite the apparently easy alternative of happy retirement.

To watch broken people try to make their way in the world, not knowing whom they can trust, is much more intriguing than many of the fairy-tale worlds assembled for book buyers. And it's exciting to read a yarn about people operating with limited information under pressure. It's easy to sympathize with the main characters. It's particularly delightful to find one's self liking so many of the characters who are in conflict with one another. The Almost Girl is a fun read, and the perspectives from which it draws are surely as accessible to those who are still struggling through their teen years as to those of us who see them only in a rear-view mirror.

Content Warning

It's a tradition at The Jaded Consumer to provide a content warning to readers who might be set off by contact with some pet peeve that might not be revealed in a cursory overview or a read of the back-cover copy. Content warnings don't imply a book isn't a good read – but what book is for all people? Eliza Crewe's Cracked was extremely hard to put down, though its review included a warning for people who want their urban fantasy without central, overt religious content of the sort that began bothering a small set of Jim Butcher's readers some years back once The Dresden Files got underway. The review of Steven Brust's and Skyler White's The Incrementalists notes that readers unwilling to tolerate real-world political commentary in their fantasy might want to look into the authors' politics before delving in. They're wonderful books, but like Neil Gaman's shirt says,

de gustibus non est disputandum. (There's no accounting for taste; literally, "there's no argument about the hors d'oeuvres." The brain cross-section shirt really gives new life to the old quote.) As with the review of The Incrementalists, effort is spent to prevent this section from consuming undue space.

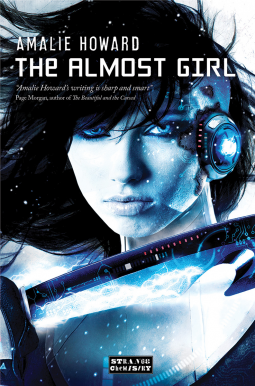

The Almost Girl is a book is about people and their relationships and their conflicts. It is not a book about technology or security. If you are a hard-core sci-fi fan who expects to experience shakes if high-tech super-suits from another Universe turn out to use halogen lamps for external illumination, or you think you will be unable to read further if that civilization manufactures thermometers that show temperature measurement that make senses to those of us who grew up using the Fahrenheit scale, you may want to think carefully before upsetting yourself. If you're a military reader with unshakable convictions regarding sentry removal techniques or security procedures, you may need to take a chill pill before getting too far into The Almost Girl. The cover evokes a delightful cyberpunk vibe, and it may attract scifi readers with demanding expectations regarding the made-up gadgets and technologies that inevitably color such work, and it is to some of these folks to whom the warning is largely directed.

Unless your OCD is out of control, or you have a special peeve involving the above, you should enjoy the book juuuust fine.

Conclusion

The Almost Girl uses an impending inter-dimensional war – and the need to keep ahead of a

dimension-shifting cadre of conscienceless fast-zombies in supersuits

(but no, says the narrator, there's no such thing as zombies) – to raise the stakes on a plausible-feeling teen suffering otherwise ordinary-looking stresses involving boy/girl interactions and siblings and parents and classes and teachers. There's lots of action, to be sure. But the best gem in The Almost Girl is the work we all have in life, to find a place for ourselves however crazy it gets. Amelie Howard's world is just painted a little crazier than yours. It's worth a visit.

Saturday, December 14, 2013

Friday, December 6, 2013

Criminal (in)Justice System At Work

Perhaps you've heard that Michael Morton was freed after almost twenty-five years in prison for a crime he didn't commit. Good news, that.

But the other side of the story is ugly. After intentionally withholding physical evidence and witness statements that would have shown the prosecutor's alligator tears (yes, he cried while imploring the jury to convict) begged for the conviction of the totally wrong man – one the suppressed eyewitness confirmed wasn't present – it appears the state's attorney was apparently so busy doing similar work with so many other cases in order to keep his prosecution rate up that he was unable to recall any details of the Morton case. Because, you know, they were like every other case in which he needed a conviction. The state's lawyer, Ken Anderson, went on to become a judge. Because the purpose of the machine is to get convictions, and success is rewarded with advancement.

Never mind that the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct expressly bar the behavior brought to light by attorneys working for free or with charitable funding to undo the evil committed by the state with the public's tax revenue. Never mind that prosecutorial irregularities are, in fact, regular. I suppose it's nice that Ken Anderson lost his law license over this, but how many lives did he wreck before he was caught? Certainly the next murdered woman – whose killer wasn't being sought because Ken claimed he had the right man when it was obvious from the witness testimony and concealed physical evidence that he didn't – would claim her life was affected. But what about all the other bogus convictions, the plea deals forced on people too terrified to risk their fates to a system bent on consuming their freedoms, the fortunes in defense costs required by bogus prosecutions?

And what about real crimes the district attorney's can't be bothered to prosecute – embezzlements by business partners, white-collar crimes that affect whole communities, and other less-than-first-degree crimes – what happens when they go unattended because all available resources are expended shooting fish in a barrel using tainted prosecutions to destroy lives that aren't protected by unlimited defense budgets?

The system needs serious work.

But the other side of the story is ugly. After intentionally withholding physical evidence and witness statements that would have shown the prosecutor's alligator tears (yes, he cried while imploring the jury to convict) begged for the conviction of the totally wrong man – one the suppressed eyewitness confirmed wasn't present – it appears the state's attorney was apparently so busy doing similar work with so many other cases in order to keep his prosecution rate up that he was unable to recall any details of the Morton case. Because, you know, they were like every other case in which he needed a conviction. The state's lawyer, Ken Anderson, went on to become a judge. Because the purpose of the machine is to get convictions, and success is rewarded with advancement.

Never mind that the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct expressly bar the behavior brought to light by attorneys working for free or with charitable funding to undo the evil committed by the state with the public's tax revenue. Never mind that prosecutorial irregularities are, in fact, regular. I suppose it's nice that Ken Anderson lost his law license over this, but how many lives did he wreck before he was caught? Certainly the next murdered woman – whose killer wasn't being sought because Ken claimed he had the right man when it was obvious from the witness testimony and concealed physical evidence that he didn't – would claim her life was affected. But what about all the other bogus convictions, the plea deals forced on people too terrified to risk their fates to a system bent on consuming their freedoms, the fortunes in defense costs required by bogus prosecutions?

And what about real crimes the district attorney's can't be bothered to prosecute – embezzlements by business partners, white-collar crimes that affect whole communities, and other less-than-first-degree crimes – what happens when they go unattended because all available resources are expended shooting fish in a barrel using tainted prosecutions to destroy lives that aren't protected by unlimited defense budgets?

The system needs serious work.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)