Despite supporting GPS for less than a year, Apple's iPhone offers more location-aware applications -- and at better prices -- than its main smartphone competitor, RIMM. The "which platform has the most apps" metric is interesting to see applied in Apple's favor. Long have Apple's fans argued that the fact Apple's platform had fewer applications didn't mean the platform wasn't as useful or as capable, and suggested that a quality-not-quantity approach should be considered. However, the iPhone allows Apple to harness the quantity metric in its favor -- something it hasn't been able to do since ... oh ... the iPod. (Being squeezed down to under 90% share is a problem more historically associated with Microsoft.)

Interestingly, Apple's volume appeal seems reinforced by a decision by Wal-Mart to create Apple sections in its retail stores. Part of an initiative to create larger, more interactive electronics sections, the Apple sales channel will apparently seek to add high-margin electronics (and maybe subscription kickbacks) to the volume retailer's historic low-margin/high-volume commodity business.

Time was, Apple's absence in the big-box stores was cited as evidence it was still a niche product. Maybe Apple is becoming more mainstream than we'd expected.

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Monday, May 18, 2009

Apple Offers Past As Future?

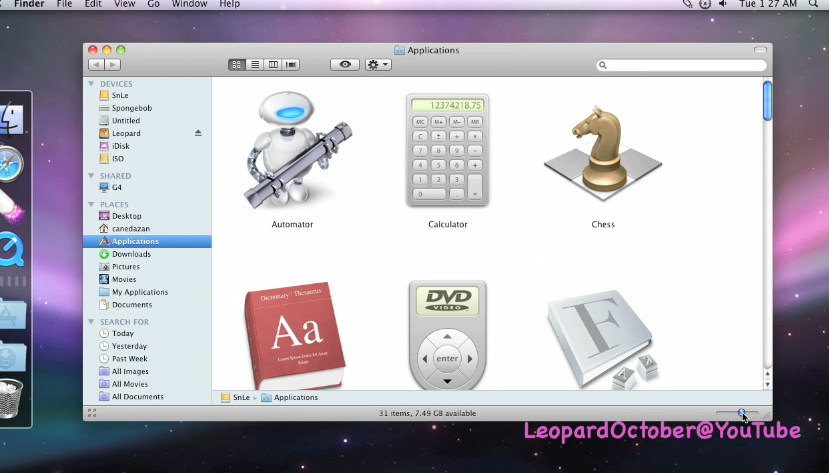

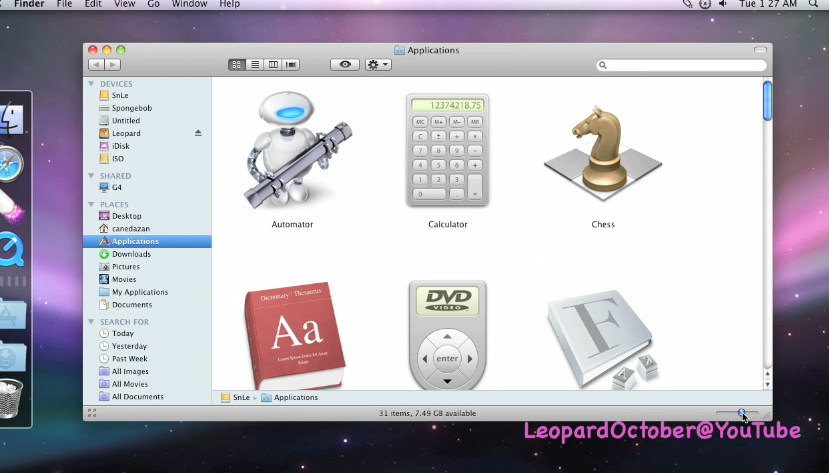

In this Google translation of a Portuguese page discussing the next version of MacOS X, I was amused to see that Finder windows will apparently contain a slider for controlling the size of applications' icons when folders are presented in icon view:

The Jaded Consumer notes that this is a feature IRIX (SGI's Unix running an X-Windows shell) offered standard in 1995. It was IRIX and its X-Windows GUI that first persuaded me that the firm that made user-friendly Unix would be in a position to make a mainstream operating system that would work -- a competitor to MSFT's offerings, and a solution to the high-overhead alternatives that have so long kept people warring with their machines to work.

Now that MacOS X allows the Finder (at least in some views) to display file names as long as Apple will allow you to name files (so you can make windows configured for you to compare files with such names), MacOS X has caught up to most of the best features offered by OS/2. (The per-folder custom background image might not be available, but exactly how necessry was that? By contrast, reading your file names without scrubbing the mouse over every file in a folder of hundreds is useful.) Catching up with the eye-candy of SGI's 1995 X-Windows might not be earth-shattering, but maybe in a way it's progress. (Considering that icons of PDFs look like the PDF, and icons of photos look like the photos, this is actually much more useful now than years ago when photos and PDFs were generic icons; thumbnail views of photos was the reason IRIX' GUI allowed scaling, if I recall.)

More important in Snow Leopard will be stem-to-stern 64-bit kernels and their associated improvements in in-kernel handling of memory (no more 32-bit kludges for RAM over 4GB, I hope). Performance improvements long postponed out of fear of breaking drivers that depended on in-kernel memory structures will materialize: since every driver needs recompiling, there's no reason to be held back by anyone's ancient drivers. Since my printer is supported by CUPS, there's no fear I'll have to replace it, either: CUPS will be provided in Snow Leopard, and CUPS will read the printer description file provided for my old LaserJet 6L, so all will be right as rain.

If Apple starts offering per-folder background image preferences, I'll have to start wondering where Apple got an OS/2 engineer. Until then, I think Apple's on a path toward improvement.

Incidentally, MSFT's price-based advertising (first discussed in connection with its "white paper") has hit a new snag: their featured "real-world" computer buyers and their interviews appear likely to be blatantly canned, and thus a sham. Apple's return punch doesn't pretend to offer non-actor shoppers, but is plainly in line with its existing line of "Get a Mac" advertisements starring John Hodgman.

The Jaded Consumer notes that this is a feature IRIX (SGI's Unix running an X-Windows shell) offered standard in 1995. It was IRIX and its X-Windows GUI that first persuaded me that the firm that made user-friendly Unix would be in a position to make a mainstream operating system that would work -- a competitor to MSFT's offerings, and a solution to the high-overhead alternatives that have so long kept people warring with their machines to work.

Now that MacOS X allows the Finder (at least in some views) to display file names as long as Apple will allow you to name files (so you can make windows configured for you to compare files with such names), MacOS X has caught up to most of the best features offered by OS/2. (The per-folder custom background image might not be available, but exactly how necessry was that? By contrast, reading your file names without scrubbing the mouse over every file in a folder of hundreds is useful.) Catching up with the eye-candy of SGI's 1995 X-Windows might not be earth-shattering, but maybe in a way it's progress. (Considering that icons of PDFs look like the PDF, and icons of photos look like the photos, this is actually much more useful now than years ago when photos and PDFs were generic icons; thumbnail views of photos was the reason IRIX' GUI allowed scaling, if I recall.)

More important in Snow Leopard will be stem-to-stern 64-bit kernels and their associated improvements in in-kernel handling of memory (no more 32-bit kludges for RAM over 4GB, I hope). Performance improvements long postponed out of fear of breaking drivers that depended on in-kernel memory structures will materialize: since every driver needs recompiling, there's no reason to be held back by anyone's ancient drivers. Since my printer is supported by CUPS, there's no fear I'll have to replace it, either: CUPS will be provided in Snow Leopard, and CUPS will read the printer description file provided for my old LaserJet 6L, so all will be right as rain.

If Apple starts offering per-folder background image preferences, I'll have to start wondering where Apple got an OS/2 engineer. Until then, I think Apple's on a path toward improvement.

Incidentally, MSFT's price-based advertising (first discussed in connection with its "white paper") has hit a new snag: their featured "real-world" computer buyers and their interviews appear likely to be blatantly canned, and thus a sham. Apple's return punch doesn't pretend to offer non-actor shoppers, but is plainly in line with its existing line of "Get a Mac" advertisements starring John Hodgman.

Thursday, May 7, 2009

New Flu Spotlights Little-Known Evolutionary Trick

The new flu shows big evolutionary changes can occur virtually overnight.

The influenza virus recently in the news -- first known as a "swine flu" then rebadged as H1N1 2009 to better identify it with comparison H1N1 influenzas and to protect hog farmers and the hogs themselves from public backlash -- represents a change (i.e., a mutation) that is not the kind of point-mutation "accident" most commonly understood to create change in a genome over time. Known as "reassortment", the trick that combined genetic material from several different influenza strains -- strains with known origins in three different host species, namely human, swine, and avian -- enables a strain in one step to take on genetic material with a proven track record developed in an entirely different virus population. Instead of changing one base pair at a time -- which may allow slow drift of a genome, or may simply produce a dead-end that doesn't work -- this process enables huge genetic changes in a single generation.

These dramatic changes can mean improved avoidance of host population defenses built up against predecessor agents of infection. Reassortment has thus been identified as a factor in major epidemics -- that is, sudden population-level problems coping with the dominant virus strain, and the replacement of the dominant virus strain with a successor -- over the last century.

The existence of sudden mechanisms of significant genetic alteration offers some interesting food for thought as we consider periods of time in which our planet has experienced an apparently accelerated speciation. New species, perhaps more resistant to prevailing illnesses or more capable of competing for food, might displace existing species with relative speed. New pathogens might crush longstanding species' public-health-free populations, creating opportunities for creatures that could not compete until hardiness from new illnesses became a competitive advantage. Collapse of certain species might have ripple effects across an environment, creating new opportunities for naescent competitors.

Debates will doubtless continue over just how major population collapses occurred, or the reasoning behind major speciation events. It is certain that argument will continue over even the existence of speciation through the mechanism of evolution. (Interestingly, however, I have not yet heard any alternate theory to explain speciation. Presumably -- if non-evolutionary theory is to be accepted -- there is every so often another Creation, isolated so one or isolated parts of the globe, to produce whatever new species might emerge there. I haven't seen any particular evidence gathered for this kind of claim; much less, I haven't even heard the apparently-necessary claim.)

Reassortment, or other mechanisms such as transposons that enable single-step alterations much greater in scope than mere point mutations, and can even allow cross-species importation of survival-proven genetic material, absolutely torpedo the claim of Mr. Berlinski -- that the theory of evolution "requires for every significant morphological or physiological feature in a modern species ... a panoply of intermediate forms that explains how they arrived." Since massive single-generation genetic changes would not leave a "panoply of intermediate forms" there is no reason to expect such a "panoply of intermediate forms[.]" Such a presentation of "intermediate forms" would not explain how they arrived, they would only illustrate one possible effect of a series of related point mutations. When mutation mechanisms other than simple point mutations are considered, it's obvious that Mr. Berlinski's argument is bankrupt, and capable only of fooling those who have no idea what kinds of mechanisms might underlie mutation.

The important thing is that we continue to collect and evaluate evidence -- without which we have little hope of understanding the rules that govern the world around us. Why the rules are as they are is of course a matter of faith, and philosophy. However, I have grave doubts about any system of belief that requires people to turn a blind eye to the evidence available in the world about them. If humans live with some purpose, surely this purpose does not require each member of the species to shrink from having a close look at the world about. Particularly if from the earliest record we were called upon before all other tasks to give a name to all the species, then to cultivate the place where we were delivered to live, we should be making some non-trivial effort to understand what the species are so they can be named, and to learn what might be learned about the cultivation of the resources entrusted to us so that we may do a competent job of it.

Falling to bickering over why there are species seems backward when we have yet to understand fully how they are made and what the result has been -- both of which would presumably be a source of insight into that why question, evidencing its answer like little else.

The influenza virus recently in the news -- first known as a "swine flu" then rebadged as H1N1 2009 to better identify it with comparison H1N1 influenzas and to protect hog farmers and the hogs themselves from public backlash -- represents a change (i.e., a mutation) that is not the kind of point-mutation "accident" most commonly understood to create change in a genome over time. Known as "reassortment", the trick that combined genetic material from several different influenza strains -- strains with known origins in three different host species, namely human, swine, and avian -- enables a strain in one step to take on genetic material with a proven track record developed in an entirely different virus population. Instead of changing one base pair at a time -- which may allow slow drift of a genome, or may simply produce a dead-end that doesn't work -- this process enables huge genetic changes in a single generation.

These dramatic changes can mean improved avoidance of host population defenses built up against predecessor agents of infection. Reassortment has thus been identified as a factor in major epidemics -- that is, sudden population-level problems coping with the dominant virus strain, and the replacement of the dominant virus strain with a successor -- over the last century.

The existence of sudden mechanisms of significant genetic alteration offers some interesting food for thought as we consider periods of time in which our planet has experienced an apparently accelerated speciation. New species, perhaps more resistant to prevailing illnesses or more capable of competing for food, might displace existing species with relative speed. New pathogens might crush longstanding species' public-health-free populations, creating opportunities for creatures that could not compete until hardiness from new illnesses became a competitive advantage. Collapse of certain species might have ripple effects across an environment, creating new opportunities for naescent competitors.

Debates will doubtless continue over just how major population collapses occurred, or the reasoning behind major speciation events. It is certain that argument will continue over even the existence of speciation through the mechanism of evolution. (Interestingly, however, I have not yet heard any alternate theory to explain speciation. Presumably -- if non-evolutionary theory is to be accepted -- there is every so often another Creation, isolated so one or isolated parts of the globe, to produce whatever new species might emerge there. I haven't seen any particular evidence gathered for this kind of claim; much less, I haven't even heard the apparently-necessary claim.)

Reassortment, or other mechanisms such as transposons that enable single-step alterations much greater in scope than mere point mutations, and can even allow cross-species importation of survival-proven genetic material, absolutely torpedo the claim of Mr. Berlinski -- that the theory of evolution "requires for every significant morphological or physiological feature in a modern species ... a panoply of intermediate forms that explains how they arrived." Since massive single-generation genetic changes would not leave a "panoply of intermediate forms" there is no reason to expect such a "panoply of intermediate forms[.]" Such a presentation of "intermediate forms" would not explain how they arrived, they would only illustrate one possible effect of a series of related point mutations. When mutation mechanisms other than simple point mutations are considered, it's obvious that Mr. Berlinski's argument is bankrupt, and capable only of fooling those who have no idea what kinds of mechanisms might underlie mutation.

The important thing is that we continue to collect and evaluate evidence -- without which we have little hope of understanding the rules that govern the world around us. Why the rules are as they are is of course a matter of faith, and philosophy. However, I have grave doubts about any system of belief that requires people to turn a blind eye to the evidence available in the world about them. If humans live with some purpose, surely this purpose does not require each member of the species to shrink from having a close look at the world about. Particularly if from the earliest record we were called upon before all other tasks to give a name to all the species, then to cultivate the place where we were delivered to live, we should be making some non-trivial effort to understand what the species are so they can be named, and to learn what might be learned about the cultivation of the resources entrusted to us so that we may do a competent job of it.

Falling to bickering over why there are species seems backward when we have yet to understand fully how they are made and what the result has been -- both of which would presumably be a source of insight into that why question, evidencing its answer like little else.

Lightning Strikes Twice ... Or Even Five Times

A West Virginia Woman named Brenda Bailey has won a government scratch-the-ticket lottery five times since September. Wins ranging from $1,000 to $100,000 now total $167,000.

She plans to pay for her pets' vet bills and some home repair, but also intends repaying people who have helped her in the past.

I ordinarily view the lottery as a tax on those bad at math, but in Brenda's case ....

She plans to pay for her pets' vet bills and some home repair, but also intends repaying people who have helped her in the past.

I ordinarily view the lottery as a tax on those bad at math, but in Brenda's case ....

Tuesday, May 5, 2009

Taxpayers' $7B Gift To Fiat

Since Chrysler won't be repaying the $7B in taxpayers' money "loaned" to Chrysler by the federal government within the last year, as the debt will apparently be extinguished in Chrysler's bankruptcy, the sum in effect has become a gift to Chrysler's new suitor Fiat. (Having taken Chrysler, Fiat is next going to gobble GM's German unit Opel. I'm betting Fiat takes it free of US taxpayer obligation, too.)

My question is fairly simple: why is it that when AIG, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac wanted federal money, they had to pony up an 80% equity stake and submit to federal oversight of fundraising activities, but when the auto makers wanted money they just stuck out their hands? Sure, legislators gave them some trash talk and spoke badly of auto makers' apparent lack of plan to turn the money into success. This fact didn't keep them from handing the auto makers billions, though -- just maybe fewer billions than initially begged for.

I guess it's easy to write those checks when it's not your money.

My question is fairly simple: why is it that when AIG, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac wanted federal money, they had to pony up an 80% equity stake and submit to federal oversight of fundraising activities, but when the auto makers wanted money they just stuck out their hands? Sure, legislators gave them some trash talk and spoke badly of auto makers' apparent lack of plan to turn the money into success. This fact didn't keep them from handing the auto makers billions, though -- just maybe fewer billions than initially begged for.

I guess it's easy to write those checks when it's not your money.

Latest ACAS Sale Closed 33% Above 4Q2008 Valuation

The recently-announced sale of Piper Aircraft turns out to offer good news beyond the mere fact ACAS still has valuable things to sell, and is able to close transactions. The first part of the next wave of insight Piper offers is that Piper represents a sale at a profit: ACAS realized $31 million on the deal. Making money is always good, right? This works against the thesis that ACAS faces a forced-sale environment. ACAS' internal rate of return of 19% is a nice return for ACAS' shareholders, and speaks well of ACAS' management of funds.

The second good news in the Piper transaction is much more important to current shareholders. After all, that prior gain was baked into the share price, right? All the current shareholders will get from a realization like a sale is a tax obligation. What current shareholders want to see -- shareholders who are looking at ACAS' below-NAV trading range and wondering whether that foreshadows more NAV collapse or portends terrific profits as prices rationalize -- is what Piper's sale means for ACAS' valuation of its assets. And here we have a red-letter day. When ACAS exited Piper -- both equity and debt -- it did so at a price 33% above the FAS-157 "fair value" of the Piper assets at the close of the 4Q2008 quarter.

The fact that ACAS-held debt is worth a lot more than FAS-157-compliant valuations suggest is something shareholders wanted to see confirmed, and this is certainly help in that direction.

Next up: ACAS' quarterly announcement for 1Q2009.

Let's see if the good news continues.

The second good news in the Piper transaction is much more important to current shareholders. After all, that prior gain was baked into the share price, right? All the current shareholders will get from a realization like a sale is a tax obligation. What current shareholders want to see -- shareholders who are looking at ACAS' below-NAV trading range and wondering whether that foreshadows more NAV collapse or portends terrific profits as prices rationalize -- is what Piper's sale means for ACAS' valuation of its assets. And here we have a red-letter day. When ACAS exited Piper -- both equity and debt -- it did so at a price 33% above the FAS-157 "fair value" of the Piper assets at the close of the 4Q2008 quarter.

The fact that ACAS-held debt is worth a lot more than FAS-157-compliant valuations suggest is something shareholders wanted to see confirmed, and this is certainly help in that direction.

Next up: ACAS' quarterly announcement for 1Q2009.

Let's see if the good news continues.

Monday, May 4, 2009

Changing America's International Tax Policy for Better or Worse

President Obama has announced plans to change United States tax law to increase taxability of overseas subsidiaries of American companies.

Let's look at how this works.

American companies which now compete in overseas markets on similar footing to their local competitors, by paying similar local tax rates and thus achieving similar after-tax returns on investment, would no longer be able to check a box to avoid U.S. taxation of those operations. Operations in many parts of the world -- those parts with higher-than-U.S. tax rates -- will be unaffected in practice because the United States would still collect no tax: the local operations would be taxed at higher local rates, and under U.S. tax treaties designed to prevent double taxation, the Internal Revenue Service would collect no further tax on those earnings. The new rule would impact businesses operating in those jurisdictions with lower-than-U.S. tax rates.

In these low-tax jurisdictions, the competitiveness of non-local business depends in part on the taxing policy of their parents' governments. American-style "we tax you on your worldwide income" policy results in taxpayers facing a 35% tax rate floor regardless where they situate operations (well, with the exception that certain economic zones carved out by Congress for special tax treatment might get better deductibility of expenses or the like; the tax code is rife with favoritism ... ask any sugar farmer). So in a 10% tax jurisdiction, local firms with $1 of profit will end up with $0.90 to reinvest after taxes, whereas an American competitor with the same performance would have $0.65 to reinvest -- assuming the jurisdiction has a tax treaty that prevents double taxation, without which the American operation would have a post-tax profit of $0.55 (after paying both U.S. federal income tax at the 35% rate and tax at the local 10% rate). The difference -- the $0.25 or $0.35 -- is unavailable to pay dividends to U.S. owners, be split into profit-sharing plans for U.S. employees, or used to uprade companies' U.S. facilities and infrastructure that make the company's worldwide operations possible.

The jump from $0.65 to $0.90 is a 38.5% gain. Improving after-tax profit by 38.5% is so attractive -- this isn't an increase in taxable income, mind you, but after-tax income, making it a much more valuable way to gain an additional $0.25 than one ordinarily is able -- that organizations facing this situation have a very powerful motive to avoid the extrajurisdictional tax. (In the case of a jurisdiction without a tax treaty with the U.S. to prevent double-taxation of income, the motivation becomes much more severe -- as it does in the case of a foreign jurisdiction with an even lower tax rate wuch as 5%, 3%, or 0%.) Careful evaluation of the tax rules will always turn up ways to avoid unnecessary taxation, because the rules for taxing incomes have never been simple -- especially across the borders of countries with which the United States has tax treaties.

Tax avoidance is not the same as tax evasion: it's lot a lie told to prevent government from learning the true extent of one's tax obligation, it's a decision to structure transactions in such a way as to enjoy the benefit of the tax rules. As a hypothetical, imagine a corporate owner deciding not to pay himself a multimillion dollar salary (which would be taxable as ordinary income) but to richly fund an employee benefit plan (which depending on the type of benefit could be exempt from taxes, could result in deferral of tax payment until some future distribution date, or could be a deductible expense and thus paid for with pre-tax dollars) while reinvesting against the day he sells his shares (for a long-term capital gain, taxed at a more favorable rate). This decision would be tax avoidance, not evasion: it requires neither deceit nor illegal activity to conduct. It's why companies engage in tax planning. Tax planning is a big high-dollar business -- precicely because every dollar saved with tax planning is an after-tax dollar.

The expected outcome of international tax planning in the face of the proposed checkbox elimination is not difficult to imagine: fewer U.S. companies doing international business through foreign subsidiaries. Instead, foreign-sited business (whose owners would include, perhaps in numerous minority stakes, Americans who used to do business abroad directly) would do business in the U.S. through owned subsidiaries, if at all, with the rest of their worldwide operations never touched by American tax laws. Efforts to attch U.S. income taxation to listings on major exchanges is sure to fail: major exchanges include numerous foreign corporations' ADRs (American Depository Receipts) that trade just like shares, and the United States would be unable to reach them with U.S. tax laws. It would be hard to see how Americans structuring foreign public companies with US-traded ADRs would fare differently, unless we restructured the rules to make non-US companies prefer to trade on some non-US exchange. (How's that for progress?)

Americans would continue to compete against all comers at home, but would generally not compete abroad. Americans who employ tax advisors would organize operations so that all non-US business was conducted through entities that never did any business in the United States (other than perhaps through subsidiaries or partners which would bear the U.S. taxes) and thus never fell within the reach of U.S. tax laws. Certainly, some businesses with highly-concentrated ownership would be unable to appear non-US in nature and would be stuck with worldwide U.S. taxation -- family businesses, for example -- but the really big organizations would presumably be able to structure their affairs to avoid U.S. taxes until U.S. tax law finally attempted to tax on their worldwide incomes all corporations wherever situated regardless who owned them and regardless whether they ever did any business in the United States. However, the 38% increase in after-tax income will surely draw multiple owners into collaboration to co-own foreign entities in small minority slices, for the express purpose of gaining an overnight 38.5% increase in take-home profits.

Assuming that U.S. tax law doesn't soon purport to tax on their worldwide incomes all corporations wherever situated regardless who owned them and regardless whether they ever did any business in the United States, avoidance of U.S. taxes by firewalling U.S. operations from foreign holding companies is likely to be the principal result of eliminating the checkbox. More money will be made by those who offer tax advice and structure international business organizations, but not much more will be collected by the Internal Revenue Service (except through increased income taxes collected from tax advisors enriched by harshening U.S. tax policy).

Assuming we don't want to lose American competitiveness abroad, we should be looking at ways to ensure foreign profits come home, not ways to ensure they are punished.

Unfortunately, American efforts to control markets have a pretty bad history of improving the status of foreign competitors. We wanted to reduce the number of physicians in the U.S., so we reduced funding for seats in medical school -- reducing U.S.-trained physicians. Of course, residency programs still want trainees to do work in their programs, so we import non-US physicians every year by the thousand. Foreign-trained medical students unable to get into U.S. medical schools have become so ubiquitous that they are a stock figure in caricatures of the modern medical establishment. Why are we helping foreigners to get high-dollar prestige jobs here in the U.S. at the expense of Americans, able to speak English intelligibly, who would happily have done similar work had medical schools not been shrunk in favor of foreign grads?

Our investment in education isn't just enhancing the stock of foreign medical grads. Bill Gates famously called for abolishing federal H-1 visa quotas on the ground that the U.S. wasn't producing enough programming talent. The United States invented programming talent. Why is it we can't be bothered to make training accessible to locals?

Presumably we don't plan to save America by contracting the job to foreigners. Let's think of a plan that does something more sensible, and keeps the money (and the pride) at home.

Let's look at how this works.

American companies which now compete in overseas markets on similar footing to their local competitors, by paying similar local tax rates and thus achieving similar after-tax returns on investment, would no longer be able to check a box to avoid U.S. taxation of those operations. Operations in many parts of the world -- those parts with higher-than-U.S. tax rates -- will be unaffected in practice because the United States would still collect no tax: the local operations would be taxed at higher local rates, and under U.S. tax treaties designed to prevent double taxation, the Internal Revenue Service would collect no further tax on those earnings. The new rule would impact businesses operating in those jurisdictions with lower-than-U.S. tax rates.

In these low-tax jurisdictions, the competitiveness of non-local business depends in part on the taxing policy of their parents' governments. American-style "we tax you on your worldwide income" policy results in taxpayers facing a 35% tax rate floor regardless where they situate operations (well, with the exception that certain economic zones carved out by Congress for special tax treatment might get better deductibility of expenses or the like; the tax code is rife with favoritism ... ask any sugar farmer). So in a 10% tax jurisdiction, local firms with $1 of profit will end up with $0.90 to reinvest after taxes, whereas an American competitor with the same performance would have $0.65 to reinvest -- assuming the jurisdiction has a tax treaty that prevents double taxation, without which the American operation would have a post-tax profit of $0.55 (after paying both U.S. federal income tax at the 35% rate and tax at the local 10% rate). The difference -- the $0.25 or $0.35 -- is unavailable to pay dividends to U.S. owners, be split into profit-sharing plans for U.S. employees, or used to uprade companies' U.S. facilities and infrastructure that make the company's worldwide operations possible.

The jump from $0.65 to $0.90 is a 38.5% gain. Improving after-tax profit by 38.5% is so attractive -- this isn't an increase in taxable income, mind you, but after-tax income, making it a much more valuable way to gain an additional $0.25 than one ordinarily is able -- that organizations facing this situation have a very powerful motive to avoid the extrajurisdictional tax. (In the case of a jurisdiction without a tax treaty with the U.S. to prevent double-taxation of income, the motivation becomes much more severe -- as it does in the case of a foreign jurisdiction with an even lower tax rate wuch as 5%, 3%, or 0%.) Careful evaluation of the tax rules will always turn up ways to avoid unnecessary taxation, because the rules for taxing incomes have never been simple -- especially across the borders of countries with which the United States has tax treaties.

Tax avoidance is not the same as tax evasion: it's lot a lie told to prevent government from learning the true extent of one's tax obligation, it's a decision to structure transactions in such a way as to enjoy the benefit of the tax rules. As a hypothetical, imagine a corporate owner deciding not to pay himself a multimillion dollar salary (which would be taxable as ordinary income) but to richly fund an employee benefit plan (which depending on the type of benefit could be exempt from taxes, could result in deferral of tax payment until some future distribution date, or could be a deductible expense and thus paid for with pre-tax dollars) while reinvesting against the day he sells his shares (for a long-term capital gain, taxed at a more favorable rate). This decision would be tax avoidance, not evasion: it requires neither deceit nor illegal activity to conduct. It's why companies engage in tax planning. Tax planning is a big high-dollar business -- precicely because every dollar saved with tax planning is an after-tax dollar.

The expected outcome of international tax planning in the face of the proposed checkbox elimination is not difficult to imagine: fewer U.S. companies doing international business through foreign subsidiaries. Instead, foreign-sited business (whose owners would include, perhaps in numerous minority stakes, Americans who used to do business abroad directly) would do business in the U.S. through owned subsidiaries, if at all, with the rest of their worldwide operations never touched by American tax laws. Efforts to attch U.S. income taxation to listings on major exchanges is sure to fail: major exchanges include numerous foreign corporations' ADRs (American Depository Receipts) that trade just like shares, and the United States would be unable to reach them with U.S. tax laws. It would be hard to see how Americans structuring foreign public companies with US-traded ADRs would fare differently, unless we restructured the rules to make non-US companies prefer to trade on some non-US exchange. (How's that for progress?)

Americans would continue to compete against all comers at home, but would generally not compete abroad. Americans who employ tax advisors would organize operations so that all non-US business was conducted through entities that never did any business in the United States (other than perhaps through subsidiaries or partners which would bear the U.S. taxes) and thus never fell within the reach of U.S. tax laws. Certainly, some businesses with highly-concentrated ownership would be unable to appear non-US in nature and would be stuck with worldwide U.S. taxation -- family businesses, for example -- but the really big organizations would presumably be able to structure their affairs to avoid U.S. taxes until U.S. tax law finally attempted to tax on their worldwide incomes all corporations wherever situated regardless who owned them and regardless whether they ever did any business in the United States. However, the 38% increase in after-tax income will surely draw multiple owners into collaboration to co-own foreign entities in small minority slices, for the express purpose of gaining an overnight 38.5% increase in take-home profits.

Assuming that U.S. tax law doesn't soon purport to tax on their worldwide incomes all corporations wherever situated regardless who owned them and regardless whether they ever did any business in the United States, avoidance of U.S. taxes by firewalling U.S. operations from foreign holding companies is likely to be the principal result of eliminating the checkbox. More money will be made by those who offer tax advice and structure international business organizations, but not much more will be collected by the Internal Revenue Service (except through increased income taxes collected from tax advisors enriched by harshening U.S. tax policy).

Assuming we don't want to lose American competitiveness abroad, we should be looking at ways to ensure foreign profits come home, not ways to ensure they are punished.

Unfortunately, American efforts to control markets have a pretty bad history of improving the status of foreign competitors. We wanted to reduce the number of physicians in the U.S., so we reduced funding for seats in medical school -- reducing U.S.-trained physicians. Of course, residency programs still want trainees to do work in their programs, so we import non-US physicians every year by the thousand. Foreign-trained medical students unable to get into U.S. medical schools have become so ubiquitous that they are a stock figure in caricatures of the modern medical establishment. Why are we helping foreigners to get high-dollar prestige jobs here in the U.S. at the expense of Americans, able to speak English intelligibly, who would happily have done similar work had medical schools not been shrunk in favor of foreign grads?

Our investment in education isn't just enhancing the stock of foreign medical grads. Bill Gates famously called for abolishing federal H-1 visa quotas on the ground that the U.S. wasn't producing enough programming talent. The United States invented programming talent. Why is it we can't be bothered to make training accessible to locals?

Presumably we don't plan to save America by contracting the job to foreigners. Let's think of a plan that does something more sensible, and keeps the money (and the pride) at home.

Saturday, May 2, 2009

Obama's Supreme Court Philosophy Exactly Wrong

Today President Obama reaffirmed his commitment to ethereal touchy-feely qualifications as an overriding qualification of a new member of the Supreme Court. Citing "empathy" as the leading qualification of his nominations for spots among the nation's top jurists, Obama risks placing the outcomes of particular cases -- and non-legal ideas about who the "good guys" are -- ahead of things like the rule of law and the durability of ostensibly inalienable rights.

If courts wanted the "good guys" to win instead of enforcing the law, we'd end up at the end of the day with a popularity contest instead of consistent and predictable law on which one could plan one's personal and business future. Imagine for a moment that whether you had property rights, or a right against unreasonable search and siezure, turned on whether some members of the court thought you were "good" instead of whether the search met certain criteria designed to protect citizens from an overreachign police state. Imagine that whether your property had been taken for public use depended on whether a judge had sympathy for the ostensible public use, or whether the judge thought you were being a "good citizen" while your property was threatened.

The rule of law exists -- if it exists at all -- when offensive, rough-hewn outcasts are protected as carefully from intrusions and trespass as the courts protect schoolteachers, firemen, and physicians.

We don't need "heart" on the Court, we need literacy. We need a sober capacity for imagining how a rule's application -- or withdrawal -- would affect the lives of ordinary people utterly different in sympathetic character to the poor sucker whose case has made it to the Supreme Court. This is because most people never get to the Supreme Court. We don't need the court to sort out everyone's problems -- it's too busy for that -- we need a court that will announce clear rules along which lines the entire country can be predictably governed.

We do not need a call for judges to rule for those whose plight invokes sympathy -- that's what juries are for -- we need rules that will further traditional American objectives of securing personal liberty and promoting clarity of law that prevents avoidable litigation.

"Heart" and "sympathy" are great qualities in jurors, but make little sense to praise as the leading quality of a competent jurist.

If courts wanted the "good guys" to win instead of enforcing the law, we'd end up at the end of the day with a popularity contest instead of consistent and predictable law on which one could plan one's personal and business future. Imagine for a moment that whether you had property rights, or a right against unreasonable search and siezure, turned on whether some members of the court thought you were "good" instead of whether the search met certain criteria designed to protect citizens from an overreachign police state. Imagine that whether your property had been taken for public use depended on whether a judge had sympathy for the ostensible public use, or whether the judge thought you were being a "good citizen" while your property was threatened.

The rule of law exists -- if it exists at all -- when offensive, rough-hewn outcasts are protected as carefully from intrusions and trespass as the courts protect schoolteachers, firemen, and physicians.

We don't need "heart" on the Court, we need literacy. We need a sober capacity for imagining how a rule's application -- or withdrawal -- would affect the lives of ordinary people utterly different in sympathetic character to the poor sucker whose case has made it to the Supreme Court. This is because most people never get to the Supreme Court. We don't need the court to sort out everyone's problems -- it's too busy for that -- we need a court that will announce clear rules along which lines the entire country can be predictably governed.

We do not need a call for judges to rule for those whose plight invokes sympathy -- that's what juries are for -- we need rules that will further traditional American objectives of securing personal liberty and promoting clarity of law that prevents avoidable litigation.

"Heart" and "sympathy" are great qualities in jurors, but make little sense to praise as the leading quality of a competent jurist.

Friday, May 1, 2009

Apple To Adopt XBox Strategy In EU.edu?

Microsoft's senior director of business, insights, and strategy for XBox has taken a position at Apple. A 15-year Microsoft veteran, Richard Teversham will reportedly take an education-related role in Apple's European office.

Apple's platform's easy facility with multiple languages, fonts, entry of oddball characters not in the user's ordinary keyboard map (ich könnte nie Umlauts auf dem Compaq machen), and its strengths in localization all seem to make it an attractive tool for European users, who are likelier than American users to want to create documents in multiple languages and to have users in their organization using different keyboard mappings. The new tech that might be part of a new Apple .edu push is more speculation than analysis, but makes interesting thinking.

If the .edu rumor is wrong, Teversham might in fact be involved in developing Apple's push as a gaming platform vendor. The move to Intel machines and standard graphics cards makes this easier to argue from the desktop perspective; the development of APIs to better leverage multiprocessing potential of multi-CPU/multi-GPU/coprocessor-enhanced hardware suggests Apple might seriously intend seducing high-end box-buyers with horsepower-at-the-rear-wheel measurements; and Apple's handhelds are selling an awful lot of games for a fairly weak computational device. The potential for Apple to pull another iPod -- find a niche it can dominate and grow -- using entertainment or education as its new backdrop seems at least a curiosity.

Imagine for a moment an iTunes section with textbooks for notepads. Schools would not face sunk costs for textbook purchases (remember how quickly sociology books became obsolete when it became clear the Tasaday tribe was a hoax?), but could buy updates as needed for durable machines that would support links in reference footnotes and the ability to zoom in on maps and all kinds of other features not available in ordinary textbooks (including electronic submission of time-stamped homework). Textbook publishers would race not to get frozen out of this platform, and Apple would soon have the world's largest academic bookstore.

Ahh, but then I wake up. Apple isn't going to make a tablet, is it? Everybody knows there's no money in that niche ....

But back to entertainment: in the original iPhone developer's kit demo, Apple mentioned iPhone supported 5.1 surround sound, and one of the demonstrated apps was a space-based fighter pilot game involving asteroids and other obstacles that could approach the player's virtual position in three dimensions. Apple may not have yet figured out how to take the living room, but it's clear Apple wants to do so -- where else does one expect to find a 5.1 surround setup? Apple simply hasn't yet figured out where the keystone is.

Apple's platform's easy facility with multiple languages, fonts, entry of oddball characters not in the user's ordinary keyboard map (ich könnte nie Umlauts auf dem Compaq machen), and its strengths in localization all seem to make it an attractive tool for European users, who are likelier than American users to want to create documents in multiple languages and to have users in their organization using different keyboard mappings. The new tech that might be part of a new Apple .edu push is more speculation than analysis, but makes interesting thinking.

If the .edu rumor is wrong, Teversham might in fact be involved in developing Apple's push as a gaming platform vendor. The move to Intel machines and standard graphics cards makes this easier to argue from the desktop perspective; the development of APIs to better leverage multiprocessing potential of multi-CPU/multi-GPU/coprocessor-enhanced hardware suggests Apple might seriously intend seducing high-end box-buyers with horsepower-at-the-rear-wheel measurements; and Apple's handhelds are selling an awful lot of games for a fairly weak computational device. The potential for Apple to pull another iPod -- find a niche it can dominate and grow -- using entertainment or education as its new backdrop seems at least a curiosity.

Imagine for a moment an iTunes section with textbooks for notepads. Schools would not face sunk costs for textbook purchases (remember how quickly sociology books became obsolete when it became clear the Tasaday tribe was a hoax?), but could buy updates as needed for durable machines that would support links in reference footnotes and the ability to zoom in on maps and all kinds of other features not available in ordinary textbooks (including electronic submission of time-stamped homework). Textbook publishers would race not to get frozen out of this platform, and Apple would soon have the world's largest academic bookstore.

Ahh, but then I wake up. Apple isn't going to make a tablet, is it? Everybody knows there's no money in that niche ....

But back to entertainment: in the original iPhone developer's kit demo, Apple mentioned iPhone supported 5.1 surround sound, and one of the demonstrated apps was a space-based fighter pilot game involving asteroids and other obstacles that could approach the player's virtual position in three dimensions. Apple may not have yet figured out how to take the living room, but it's clear Apple wants to do so -- where else does one expect to find a 5.1 surround setup? Apple simply hasn't yet figured out where the keystone is.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)